The Future Doesn’t Look so Bright – 16 White People Is Not a Celebration of Diversity

By Nikita Aashi Chadha

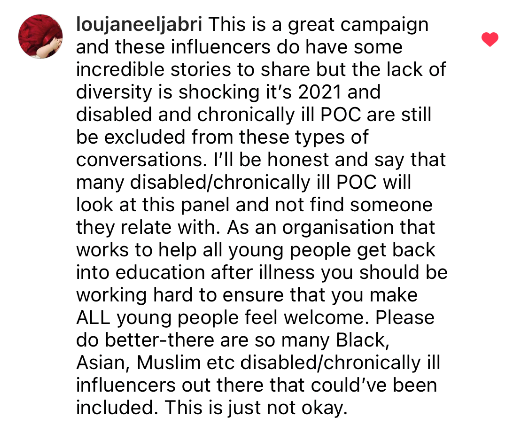

Bright Futures UK released a new campaign earlier this week, ironically named Donate2Educate, which included 16 influencers who live with chronic or long-term illnesses. My friend Neha had shared it to her IG story, reposting Loujane’s observations on how this particular collage of people wasn’t representative of chronically ill people of colour.

You can access the original post here.

Naturally, being me, I visited the post to see what the response was. Loujane had already started a meaningful dialogue with the organisation, asking them to ensure that all types of people are involved in their campaigns, knowing how many diverse influencers are active online today. She explained how most people of colour would look at this collage and feel excluded and that the organisation should be committed to ensuring that all young people felt welcomed and included. Her words really resonated with me, and I could feel the fatigue that came with constantly explaining this to organisations and people that, at this point, should know better.

People who exist in the majority, and in this case, the racial majority, think of themselves as the standard person or people. Person = white person, specifically white man (thank patriarchy). That’s why instances like this happen. Brown and Black people are ‘other; we become niche by default. If you’re white, you don’t have to worry about being underrepresented in the same way we do. But, if you’re the standard, the expected, where does that leave anyone else? Missing. Not even considered. Not for your collages or campaigns, thought processes, leadership teams – I could go on; the list is endless. We live in a racialised society, where our identity impacts everything we experience. To suggest anything else is racial gaslighting and indicative of a lack of insight or perspective. Other intersections should always be considered, of course, but race has a specific impact on every intersection of our identities.

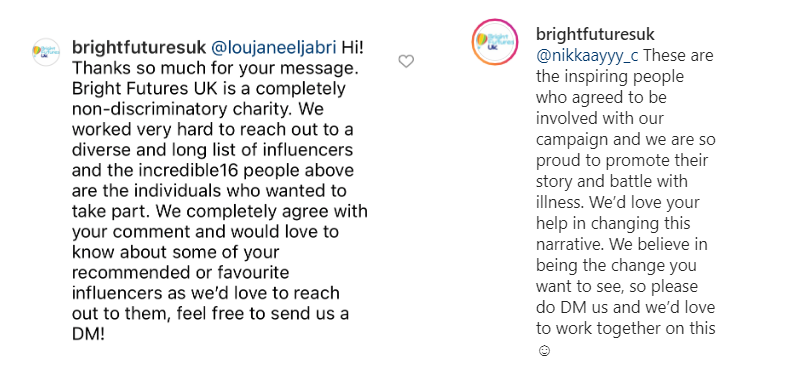

I didn’t expect much of a response. Their comments were polite enough, but I found the tone and undercurrent of the replies a little off. The language used was interesting to me. As a writer, I constantly wrestle with the impact of my written words (if only I could do the same for the words I speak, I’d get in far less trouble!). There wasn’t any responsibility, or accountability, just assertions that the people included were diverse, incredible and inspiring. I’ll start with this: no one has said that the people involved didn’t want to participate or aren’t inspiring. No one is saying that. Anyone who lives with a chronic illness is an inspiration. That feels like a deflection from the original point that several of us have come here to educate you on and has nothing to do with the point we’re making. We are all incredible here, that goes without saying. But to call these people diverse is inaccurate. This campaign is perpetuating the same old story regarding racial diversity, and it shows – that much is glaringly obvious at first glance.

I generally don’t have an issue with recommending people to follow to someone who I feel is genuinely interested, but this didn’t sit right with me either. If I tag someone, I don’t know if you’ll tokenise them or pay for their time. I don’t know how they’ll be treated or made to feel. The onus shouldn’t be on marginalised people to constantly educate you because now you want to be educated. It’s not hard to research or find people of colour to follow or support; there are plenty of hashtags and other ways to find us. There are organisations doing the work on the ground in these communities, which you can pay for consultancy, knowledge and expertise. Asking random people of colour on the internet is not the way. Lived experience is valuable. It’s something you will never have. Brown and black people shouldn’t be expected to teach others for free. White people in the D&I space speak on concepts they’ve never experienced: racism, microaggressions, etc., and they are PAID to do so. There’s a sense of entitlement in asking people to do the work for you and not pay them for their time. Especially people more minoritised than you.

Of course, I responded (how could I not at this point) about how centring whiteness is a standard within the charity sector and how white people dominate the discourse in the chronic illness space too. All spaces are white spaces unless they are curated by people of colour specifically. Brown and Black people only appear as part of diversity drives, in tokenistic ways – or not at all as this campaign proves. I understand that not every organisation has access to people or communities of colour, and I don’t expect anyone to have that. Still, there are ways to ensure that recruitment for future projects is targeted or inclusive. If you’ve reached out to 100000 people and you’ve only received responses from white people, so that’s all you include, you’re going about this all wrong. Maybe consider accessibility, things that might prevent people of colour from participating in the first place.

We all play a part in the society we live in, whether or not we like to acknowledge that. It can be challenging to do, but we have to be able to take accountability. It’s true for everyone – including me. Our world operates racially; the lighter-skinned you are, the more privilege you hold, the further your voice will travel, the more visible you are. As a brown person, I recognise that my voice travels further than anyone darker than me, even if we both exist in the same racial group. But, it doesn’t travel as far as people lighter skinned than me. We should all be committed to not letting instances like this happen again. When asked to participate in a project, especially if you belong to several majorities (or even just one): e.g. if you are white, straight, cisgender, upper class, heterosexual or able-bodied – you should be questioning who else is being included in that project. If we can challenge the campaign before it’s released, we can stop the resulting damage that ensues. If you exist in the majority, you can spotlight people with less privilege than you to be involved in opportunities for exposure. I ask specific questions whenever others approach me for my time or knowledge, more so if they represent a larger organisation. I need to know that people who look like me and more minoritised people (than me) will be included from the off-set and not as an afterthought. I don’t want to be the one brown face you use to make yourself look more inclusive when you have no real intention of creating change. I’m not your token.

I don’t know if Bright Futures did reach out to any brown or black people to participate, but I know they weren’t included. We are pretty easy to find if you know where to look. You’ll only know that if you’ve worked with us, supported us, or have been following what we do. Sometimes it’s not enough just to reach out, to have the intent of being inclusive; you have to have the follow-through, the commitment to ensuring representation across the board, even if that means paying people for their consultancy or access to communities. It’s not just about opening up the table; it’s about understanding the structural barriers that prevent certain people from having a seat at the table in the first place. If we were a priority, we’d be there. Instead, when organisations and their leadership teams all come from the same demographic, this is what happens. There is no true understanding of diversity, only tone-deaf posts and responses. And I haven’t even gotten to the way they slid into my DMs.

I don’t want to give my time, knowledge or labour educating white people or white organisations for free. I live as a brown woman every day. I encounter whiteness everywhere, even within myself and my community. Being expected to educate others further is ridiculous. What would the new awareness campaign achieve? Have we not been creating awareness, for decades, across generations? All talk and no action is dangerous.

Representation is important, of course, but it doesn’t mean anything without real commitments to change or without access to decision-making rooms and positions of power. These things have to go hand in hand. It needs to be applied top-down, accompanied by work on the ground. This organisation doesn’t care about people like me because we aren’t on their radar. I’m not about to believe any different because they’ve sent me a thoughtless message on Instagram, expecting time and labour on my behalf. After sharing the post to my story, several other people of colour messaged me to say Bright Futures had started following them. I wondered if they’d reached out directly to anyone else, but I didn’t ask. I was tired.

At this point, the message was in my requests, gathering dust. I didn’t have the initial energy to unpack it or explain why it didn’t sit well with me. It’s exhausting, having to constantly have to defend your experience perception or opinions on things. Sometimes I have to do this with other people of colour, too, because hey, we don’t all think and see things in the same way, and a lot of us enable or subscribe to whiteness in ways we don’t even consciously realise (myself included). So we also have to be dedicated to unlearning whiteness, especially the narratives we’ve internalised as children.

I was catching up with Neha (I love this babe), who told me that Bright Futures had also reached out to her. She sent me a screenshot of the message – which turned out to be the same message they’d sent me—word for word. I laughed when I saw them side by side. So here’s an organisation in my DMs claiming they want to look at real-life people and stories – but not treating us like people. No personalisation, no inclusion of names, or anything thoughtful, just a copy and paste job. Considering how much this means to them, “an awful lot”, you’d have thought they’d put more effort into it. I know our points of view are similar, like our names, ethnic origin, and maybe even us as people, but we aren’t identical. People of colour are always treated like monoliths and never individuals. Considering we took the time out of our day to educate you on your post and your mistake, you could take the time to humanise us, or maybe, learn our names?! We see behaviour like this all the time. Brown and black people are lumped together via BAME or ‘ethnic minorities’ rather than distinctive, separate groups. White people are their own race (but are also race-less in their own eyes), and anything outside of that isn’t even worth naming or acknowledging properly.

I’m writing this article mainly to warn other organisations who want to approach me, Cysters, or any of our chronically ill-warriors who are black, brown, or have further intersections to their identities. We aren’t your tick box or something to include when it suits you. We aren’t here to endlessly educate you for free when this is expertise and lived experience that white and other majority-led organisations should be paying for. It’s an insight you don’t have and that you never will, and that’s why you need to make real commitments to change.

You should be including us in your campaigns, paying us for our time, working with organisations that represent us and are already doing the work. That’s a great first step, but it’s not the be-all and end-all. Diverse people need to be represented across all societal levels, not just as unpaid advocates or tokenised trauma beacons. If every senior leadership team in the world were more diverse, campaigns like this wouldn’t even be an article topic – but yet, here we are.

*Update*

Since writing this article, I responded to Bright Futures to ask if they would be paying for my time and making an actionable commitment to change. They’ve not yet responded. I’m sure it’s not the last time I’ll be left on read…