I’ve been in a lot of places where my presence surprises people. Governmental think tank sessions, APPG working groups, overbearing corporate functions – just to name a few. When I access spaces like these, I expect to be the only person that looks like me there (or one of two). That’s the way it has always been in my experience, and even as an outspoken advocate, I find the same thing happens to me within those spaces. Fear, confusion, isolation, for a start. It’s daunting to be the ‘other’, to be glaringly reminded that your presence isn’t required but is something offered to you in the name of ‘diversity and inclusion’.

You get used to it over time. You build up defence mechanisms like small talk, smiling, but on the inside, you couldn’t feel further from that image you’re presenting externally. You psyche yourself up in the lead up to the event, and you prepare yourself for all kinds of ignorant questions and comments that you know you’ll hear or have to contend with. It takes a lot of energy, physical and mental strength. Brown and Black people are particularly resilient when navigating circumstances like these, mainly, as it happens so often (as are most marginalised or minoritised people).

Last week, I experienced being the only brown woman within a different space: during an online introduction session to a pain management course. It prompted me to want to write this piece, to say some of the things I was thinking in my head, out loud. I will start by saying that the session itself was informative and well done. They asserted throughout the session, multiple times, that those who experience chronic pelvic pain are valid, and that our pain is real. They also acknowledged that some of us may have encountered medical professionals who made us feel the exact opposite – and I thought that was quite progressive, to highlight medical gaslighting, given how prominent it is within our community. The information provided was sound and extensive, covering different types of pain, how the body responds to it, and how mental health is as much a part of healing as physical recovery.

Pain management tends to consist of physiotherapy alongside mental health intervention. Physical and mental health are interlinked, and race is an integral part of that conversation i.e anxiety and depressive disorder is much higher for South Asian women than women from any other ethnic groups (Rees et al, 2016). If I’m going to work alongside any mental health professional, they have to have a similar background or lived experience to me, because honestly, I don’t have the time to educate my therapist on racism and how it has affected my life, my identity or my self-esteem. I’m working on race and identity with my current therapist, and we’ve identified those key themes in my life, from the age of 5. This is quite a lot to contend with if you’re someone who has never experienced racism before, as an adult, let alone as a child, or throughout their lifetime.

I had other racing thoughts throughout the session: “this space is not safe” “no one understands my frame of references” “why isn’t there someone in here that I can relate to” “if I call attention to this, I will be treated differently”. Having to navigate those thoughts, and spaces that are not representative is exhausting – no matter what the context is. All of this, whilst I’m trying to take in the information being given within the session, and also the lump that’s forming in my throat because I know I’ll have to mention this and flag it to someone in charge. The defeat as I message a close friend and tell her that yet again, I don’t feel seen within the space that I’m dependent on accessing because of my multiple complicated health conditions. My palms are sweating. I’m wondering if raising this will cause a defensive reaction. Will I be labelled as a difficult patient? Will I be punished for stating something that was, to me, just incredibly obvious? I waited for the session to end and asked if I could speak to the organisers privately. I’ve learned the hard way over the years, that some conversations are better had alone, away from centre stage. Seeing as this was also regarding my health, I wanted to tread more carefully than I usually do.

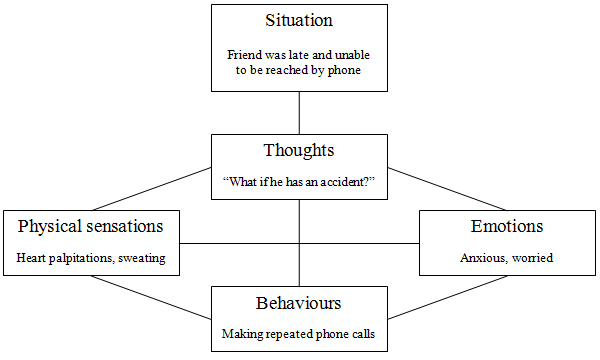

I asked politely if there was more than one mental health professional who worked within pain management, and they explained that there is generally a team on-hand. I requested that when I’m paired with a psychologist, I had a preference for a person of colour, ideally, a woman of colour. I explained my reasons why, because I think it’s important for people to understand our perspective as much as they can – race and identity are not just important to me, but they are vital to understanding my mental health, and who I am as a person. I would need to speak to someone who could understand my frame of reference and my lived experience. I gave a clear example as well i.e. we looked at the Cognitive Behavioural Therapy model during the introduction session which highlights the link between your thoughts, feelings, behaviours and actions/physical reactions. I pointed out that my formulation would be different from the other patients because they don’t have to contend with having a racialised identity. And finally, stated that being the only person of colour within a space can be quite difficult, and triggering, and that should be considered – as not everyone will speak up or mention it when it does happen.

CBT Formulation Example

The response back was warm, non-judgemental and sympathetic, and I was very grateful for that. Conversations about race, identity or privilege, can be very hard to navigate for most people. It’s designed that way, to shame or guilt us into defensiveness, apathy, and sometimes, denial. They thanked me for sharing what I did with them, and that they would note my request on my file so that it can be honoured where possible, moving forward, and acknowledged how I felt. They mentioned that usually, the sessions are more diverse, but due to people’s availability (or lack of) this particular one wasn’t.

I understand, that sometimes, for organisations or institutions – that’s just what happens on the day, and it seems like there is nothing that could be done to control or rectify it. I would have to disagree. Let’s talk about this, in the context of spaces generally, virtual or in-person. If you can identify that your service users, members or community, look predominantly the same, there are things that you can do to rectify that. Firstly, you have to see the problem. With the greatest respect in the world, most people who exist in the majority (whether that’s race, gender, sexuality, ability, class) don’t even see the lack of diversity in the first place. You can run targeted recruitment campaigns, you can work with community groups, charities or advocates that support those marginalised groups, you can consult with us on the issue and understand the barriers that may prevent different types of people from accessing your space, or service. You can simply make it a priority to ensure that the room is full of people who do not look the same or come from the same demographic.

I didn’t say all of the above. You learn when and what to say, and also to pick your battles (especially if it’s in a healthcare setting, knowing that your healthcare could be impacted and that medical professional bias is real). But I did say, again politely, that even if generally the sessions are more diverse, this one wasn’t. It may be the first time that they’ve experienced a lack of diversity, but for me, this isn’t the first time I’ve been within a space, just like this, and been the only person of colour. There will be other people in the future that may feel the same, but might not flag it, so regardless of standard practice, it had to be said, because it was felt – mainly by me. I don’t know if anyone else noticed it, or would have if it hadn’t been pointed out.

There are ways we can change this. If we’re entering new spaces, creating them, hosting or being invited into them – we can ask very simple and effective questions, that let us know how serious people are, about us, and about ensuring we’re heard and given a seat at the table.

- Am I the only person who looks like me involved in this project, or this space?

- If I am, do you have any plans to change that?

- If you don’t have any other people of colour within your networks (because this is the problem more than we realise sometimes) or in mind – I can suggest some that would be perfect for this?

I know this approach isn’t for everyone. But I believe if we all asked more questions, directly, it will prompt change because enough of us are challenging the issue, and our voices are amplified when we come together.

And finally, I hope any organisation or institutions in this country, that are creating or taking up space (whether that’s in person or virtually) will take this into account. Please look at your attendees, members, leadership boards, and ensure there is a diverse cross-reference of people, across race, gender, class, sexuality and ability, where possible. Community is important, and it’s different for all of us. My community are the people who look like me (and many who don’t at all), who experience the world in the same way I do, who understand what I’m going through. We all experience physical and mental health differently, depending on our identities, privileges, barriers – and this should be remembered, and prioritised, especially within the healthcare system. I hope one day that we’ll all be able to access spaces that make us feel safe, seen and heard.